A ‘Wuthering Heights’ adaptation as shallow as a puddle glittering in the sun

To stand even a chance at enjoying Emerald Fennell’s “Wuthering Heights,” you must let it wash over you

Every split egg yolk, every inch of snail mucus, every glistening raindrop on screen — it’s all designed to sit slickly on the surface, never going more than skin deep. The British writer and director’s third film, to be released Friday, has polarized audiences since the first trailer. Like most of the directors who have attempted to bring author Emily Brontë’s wild English moors to screen, Fennell decided to adapt only the first half of the gothic novel: cutting it off at the knees before the romance sours into a study of generational trauma.

Fennell’s version has probably 50% less plot line and characters, but 100% more fingers thrust in mouths, masturbation scenes and sex

In some ways it was set up to fail from the moment those infamous quotation marks around the title were revealed; an attempt by Fennell to get ahead of the very criticisms that have been published this week.

“I can’t say I’m making Wuthering Heights, it’s not possible,” the director said during the movie’s extensive press tour. “What I can say is I’m making a version of it.”

Look of the Week: Margot Robbie goes high-fashion Victorian for ‘Wuthering Heights’ press tour

Those quotation marks didn’t just signal subjectivity, they were a reference in themselves

In the mid-20th century, film titles regularly appeared in trailers encased in quotation marks — either to differentiate the name of the movie inside a text-crowded poster, or as a stylistic hangover from the silent film era. This cinematic standard had largely fallen away by the 1960s, but in reviving it Fennell was indicating to audiences that her film has more to do with cinematic history than it does with the Brontë parsonage.

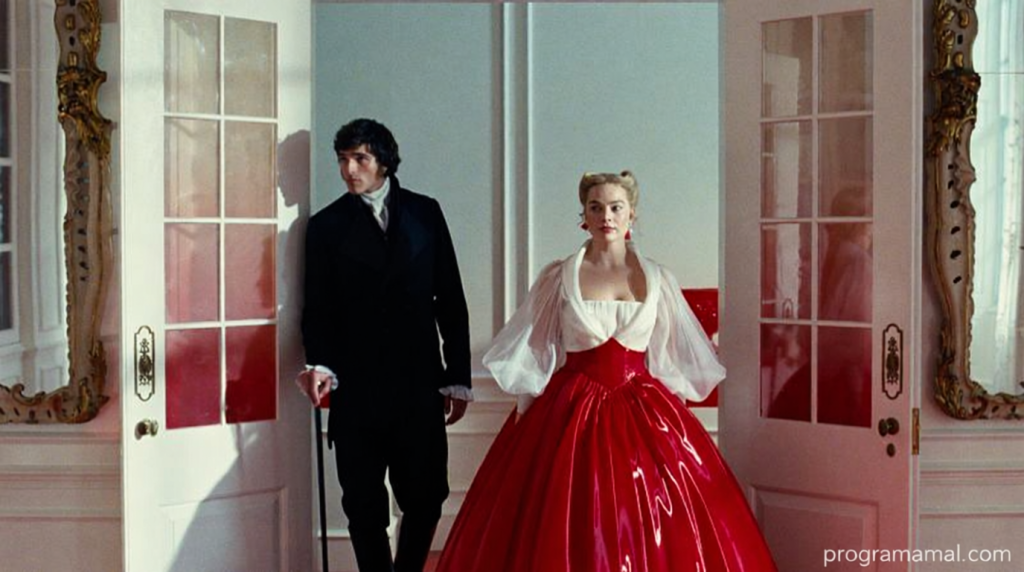

In fact, director William Wyler’s 1939 Hollywood adaptation — with its ostentatious outfits and romantic focus — feels like a better companion piece than the original literary source material. For the 2026 reimagining, Fennell worked with costume designer Jacqueline Durran to create dozens of costumes (Cathy alone, played by Margot Robbie, had 50) that were heavily inspired by the extravagant, unselfconscious and campy outfits of the mid-century.

While making the film, Fennell passed around a book inches-thick with visual references that spanned Scarlett O’Hara in “Gone with the Wind” (1939) to “Donkey Skin” (1970). If it wasn’t already obvious, period accuracy is a concept Fennell simply does not buy into.

“We all think we’re making a period drama to a point, and then it just looks like the ‘90s or whenever it was made,” she said, speaking alongside Durran at a Q&A session at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum recently. “We are making costumes. We’re making a film. That’s a suspension of disbelief that is important to acknowledge.”

Cathy’s costumes in Fennell’s film veer into Wyler territory often: she teases fellow character Isabella Linton about her doomed crush on Heathcliff in